The trade of emergency medical services is an objectively unhealthy one. Substance abuse and suicide plague providers as they experience stressful work conditions and an ever-growing burden of disease. Unhealthy healthcare workers provide poor care to patients and place them in danger of harm or death. Change is needed within the EMS community of practice to reduce harm and improve care. This paper will elucidate the barriers to healthy behavior among EMS providers and the potential benefits associated with a change in behavior.

There are a host of potential interventions with complex interactions which may have an effect on the overall health of the EMS provider population. However, it is unlikely that any intervention in isolation will have a beneficial impact. Further, there are an array of interconnected barriers preventing both meaningful intervention and engagement from EMS providers. These barriers fall into the broad categories of self-efficacy, public perception, economic stability, and social context.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy can be defined as the belief that control over one’s actions and environment can produce desirable outcomes especially when faced with novel challenges and demands.1 The ability for a medical professional to face the uncertainty of an emergent patient presentation and overcome the challenge through the process of assessment, diagnosis, and medical intervention requires a moderately high level of self-efficacy.2 Those with low levels of self-efficacy are likely to avoid the challenges associated with caring for complex patient presentations and are more prone to moral injury, stress, and depression.1,2

Current theories surrounding self-efficacy suggest a relationship between higher levels of education and a greater sense of control over one’s ability to achieve a positive outcome through action. The United States uses a vocational licensure system with a relatively short duration of training compared to other economically developed nations.3 It would seem intuitive that increasing the requirement for medical education would help boost provider self-efficacy. However, the demography of EMS providers shows an increased rate of burnout associated with higher levels of provider education.4 One possible explanation for this phenomenon is the interaction between providers with high levels of self-efficacy and the social and structural contexts of EMS care whereby EMS providers are restricted from fully actualizing their potential through negative social sanctions and legal limitations.

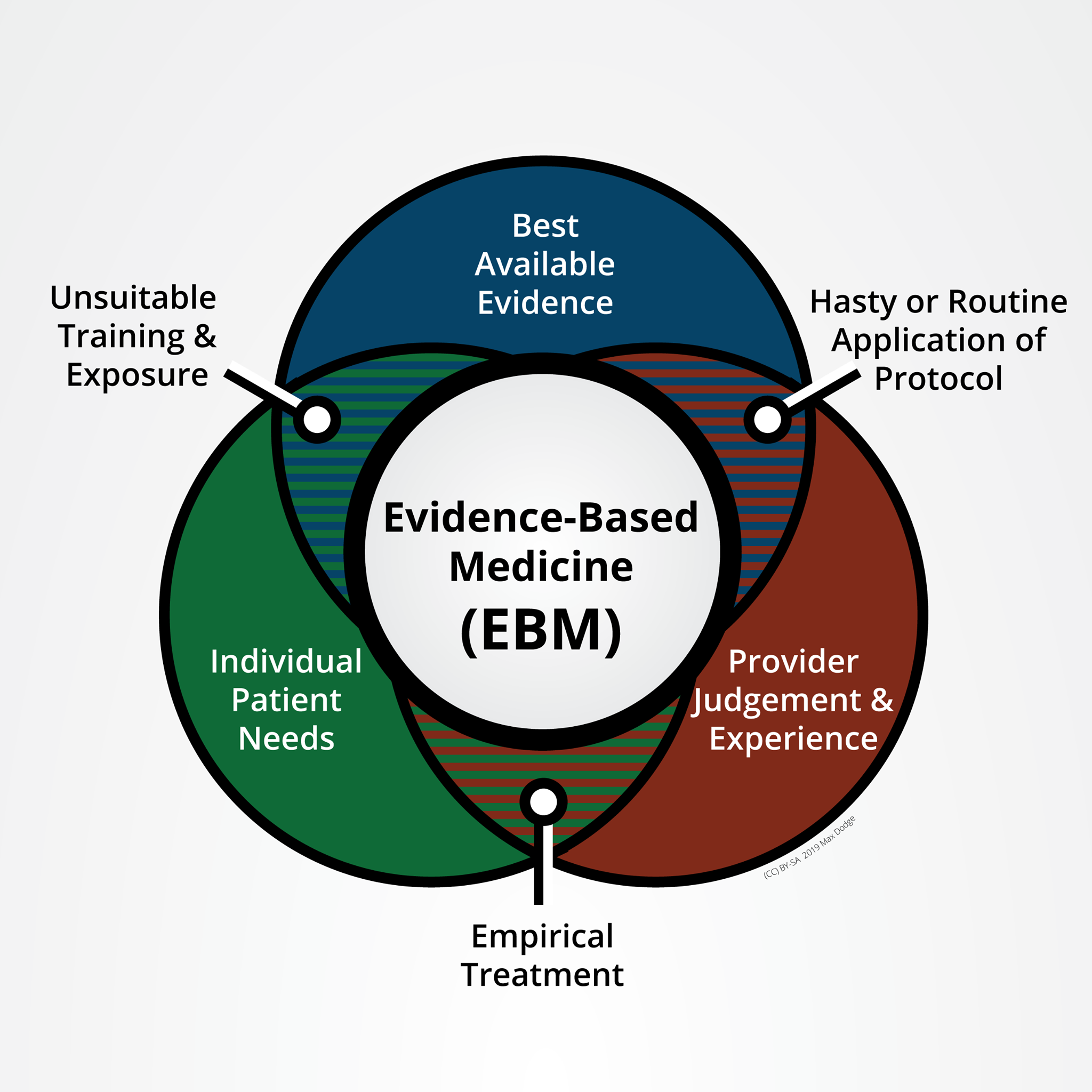

Another barrier to self-efficacy within the vocation of EMS is the fact that the standards of practice are controlled by people and organizations outside EMS. Physicians control the medical aspects of patient care using protocolized diagnosis and treatment algorithms. The education standards are defined by the U.S. Department of Transportation with consultation from external private organizations and non-medical government agencies. EMS providers are not considered the experts within their own community of practice.

Public Perception

While EMS is generally funded through property tax, a minority of people within a community will utilize emergency services. While EMS response is usually obvious due to the use of warning lights and sirens, the performance of emergency medical care goes largely unseen. Because of the separation of the population from the providers, public expectations of EMS care are not aligned with the actual capabilities of EMS systems. Citizens are overly optimistic about the timeliness of EMS response and the survival rates associated with EMS care.

A majority of polled respondents could not tell the difference between the highest and lowest levels of EMS provider, 5 commonly reducing all levels of provider to “ambulance drivers.” Recent global circumstances have improved public awareness of EMS but attempts to improve EMS working conditions have exposed misperceptions even within the governments that employ them.6

Economic Stability

The market value of emergency medical services is low. EMS providers are not considered qualified healthcare providers (QHP) by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare reimburses ambulance transport based on the mileage traveled with a patient on board and does not consider the specific types of treatments provided or the supplies used en route. Treating patients and discharging them from the ambulance back to their homes is not currently a common model in the United States, despite the proven cost-saving benefits of a Mobile Integrated Healthcare (MIH) approach.

Educational standards for EMS at all levels are managed by the U.S. Department of Transport (DOT) and the National Highway and Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA). These education standards are written as a content coverage document in lieu of educational objectives such as those used by K-12 educational institutions. The duration of training for EMS providers is measured in hours and ranges from 50 hours for an Emergency Medical Responder to 1200 hours for a Paramedic. Degrees are required for Paramedics in only two of 50 states and half of paramedic programs result in no degree. Despite strong position statements from EMS advocacy and physician organizations, the requirement for education remains low.

As a result of low education and low partial reimbursement for services, EMS wages lag far behind those in healthcare. Low wages drive a large fraction of EMS workers toward holding multiple jobs, in turn reducing the available rest and increasing the likelihood of patient care errors and patient harm.

Social Context

The work environment of most EMS systems is objectively toxic7 with a “blame and shame” culture which both hinders error reporting and is distinct from the medical field which broadly promotes risk and safety intervention. This toxic work environment increases provider stress and reduces provider self-efficacy.8 Low self-efficacy is associated with a decline in self-development activities such as seeking continuing education, which exacerbates low uncertainty tolerance2 and increases the likelihood of patient harm.

Conclusion

The issue of unhealthy EMS providers is a wicked problem with many interdependent and difficult to define factors. Any interventions undertaken must be performed in a near-simultaneous fashion with ample time, talent, and treasure from stakeholders with a deep understanding of both the complexities and the risks if interventions were to fail. Any low-level intervention targeting EMS providers would be nearly futile without strong policy and institutional support. Future writing will focus on high-level upstream policy interventions with a likelihood of creating meaningful cultural and institutional change.

References

- Warner LM, Schwarzer R. Self‐efficacy and health. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology. September 2020:605-613. doi:10.1002/9781119057840.ch111

- Hillen MA, Gutheil CM, Strout TD, Smets EMA, Han PKJ. Tolerance of uncertainty: Conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;180:62-75. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.024

- Chang YT, Tsai KC, Williams B. What are the educational and curriculum needs for emergency medical technicians in Taiwan? A scoping review. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:649-667. Published 2017 Sep 22. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S140839

- Rivard MK, Cash RE, Mercer CB, Chrzan K, Panchal AR. Demography of the national emergency medical services workforce: A description of those providing patient care in the Prehospital Setting. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;25(2):213-220. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1737282

- Crowe RP, Levine R, Rodriguez S, Larrimore AD, Pirrallo RG. Public perception of emergency medical services in the United States. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2016;31(S1). doi:10.1017/s1049023x16001126

- Sanders A. NYC coronavirus pandemic ‘not the time’ to raise pay for EMTs and paramedics: Mayor de Blasio. New York Daily News. April 3, 2020. Retrieved on September 21, 2021 from: https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-pay-raise-emts-paramedics-fdny-ems-20200403-3lqgfio3rfg2xa2o6mqpanzi6e-story.html

- Fairbanks RJ, Crittenden CN, O’Gara KG, et al. Emergency medical services provider perceptions of the nature of adverse events and near-misses in Out-of-hospital Care: An Ethnographic view. Acad Emer Med. 2008;15(7):633-640.

- Burgard SA, Lin KY. Bad jobs, bad health? How work and working conditions contribute to health disparities. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013;57(8):1105-1127. doi:10.1177/0002764213487347

- Assari S. General self-efficacy and mortality in the usa; racial differences. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2016;4(4):746-757. doi:10.1007/s40615-016-0278-0