Emergency medical services (EMS) provide care and transportation for over 20.7 million patients per year.1 EMS providers commonly experience emotional and physical stress which places them at increased risk of disease, disability, and death.2 A strong correlation exists between unhealthy medical providers and poor patient care.3 Poor health and provider burnout contribute to high rates of employee turnover, reducing staffing and placing strain on EMS systems, further reducing patient care capacity.4 The current state of health for EMS providers represents a risk to public health but has not yet been comprehensively evaluated in the literature.

EMS providers have a high burden of preventable disease related to occupational and lifestyle factors. Chronically stressful working conditions contribute to psychological and metabolic disorders. EMS providers have an increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress syndromes, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and fatigue, experiencing a 39% higher rate of suicide compared to the general population.5,6 The prevalence of alcohol and substance abuse among EMS providers is both concerning and likely underreported.7,8 Obesity and cardiovascular disease among EMS providers in the Southern United States appears to be exacerbated by a lack of physical exercise, the effects of chronic stress, and perceived barriers to health-protective behaviors.9,10

An oft-cited report from what was the Institute of Medicine found that as many as 98,000 people died as a result of preventable medical error in the latter quarter of the 20th century.11 In 2013 that number approached over 400,000 due in part to methodological improvements and an expanded definition of preventable adverse events (PAE).12 The incidence of PAE in the out-of-hospital environment is not well studied. There is evidence that rates are equal or higher than those in-hospital, and reporting of PAE and near-miss events is low. Low reporting appears to be related to the complex environment and a culture of “blame and shame”.13

The relationship between healthcare provider wellness and quality of patient care is well established. Provider burnout is the result of prolonged exposure to occupational stress and results in emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced feeling of professional efficacy.14 Though not extensively studied, there seems to be a correlation between provider burnout and PAE.15 It may therefore be reasonably concluded that EMS provider burnout and by extension the poor health of EMS providers represents a threat to public health.

Social Determinants of Health Among EMS Providers in the United States

The World Health Organization defines SDOH as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.” This definition is important to unpack because a majority of EMS providers are white, non-Hispanic people16 and are not born into the structural and interpersonal racism behind much of the health disparity in the United States. However, upon entering the EMS workforce, providers may quickly succumb to the toxic work environment surrounding them. Living, working, and aging in this toxic environment may have untoward effects on health. Using the five social determinants of health (SDOH) domains as identified in the Healthy People 2030 Framework, this paper will propose potential sources of health disparity in EMS providers.

Education Access and Quality

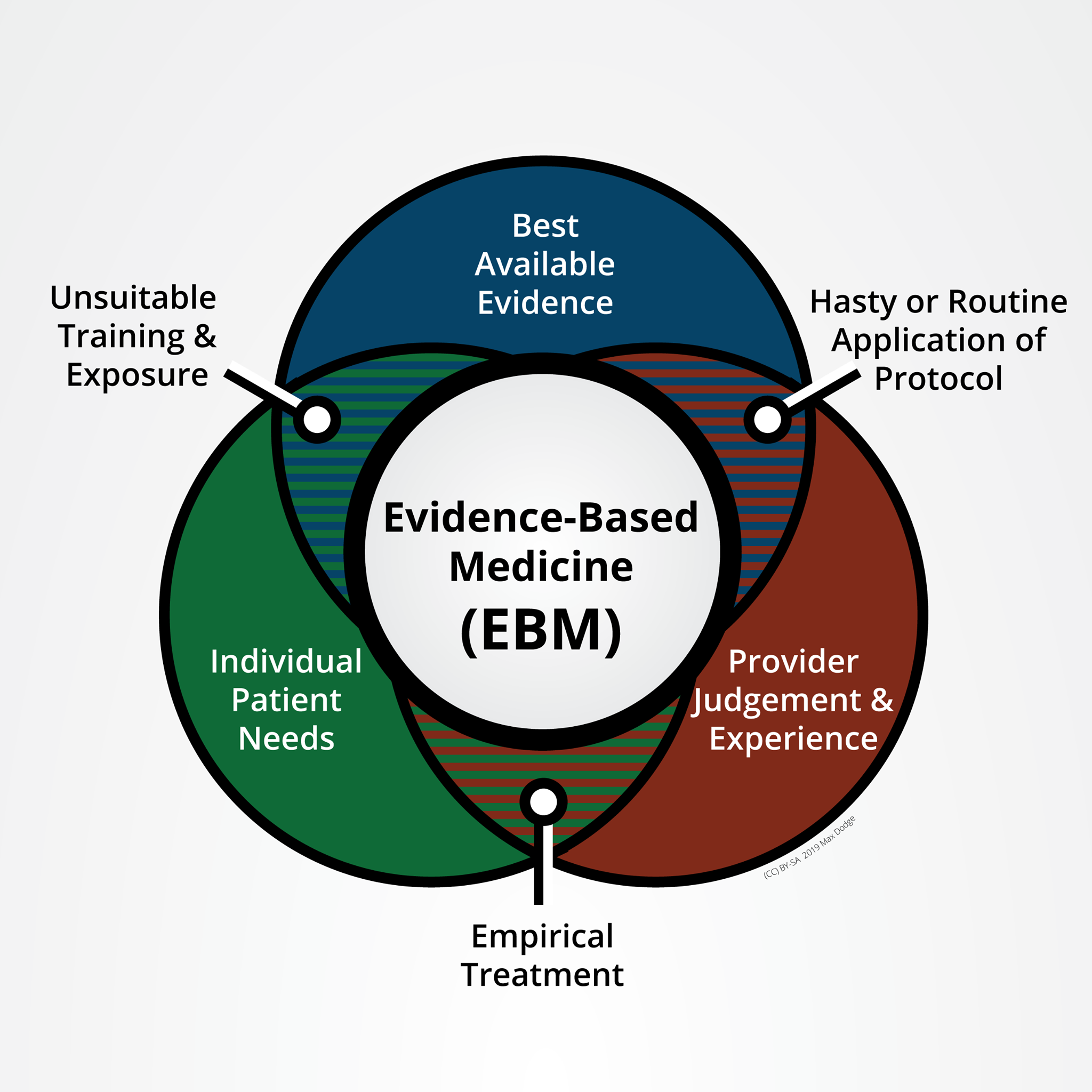

The national standards for EMS education in the United States are the lowest among nations with similarly developed economies. With the duration of training ranging between 50-1500 hours17 and no standardized residency requirements before licensed practice, EMS providers find themselves delivering emergency medicine with significantly limited clinical decision-making abilities. While the relationship between lower levels of clinical competence and higher levels of burnout has been studied in other health professions18, there are sparse data within the profession of EMS. It is possible that insufficient EMS education increases the level of chronic stress and burden of disease on providers while simultaneously placing patients at risk of PAE.

A complicating factor with regard to increasing education requirements for EMS providers is the associated increase in burnout with the attainment of a college degree.16 One possible explanation is that degree-holders recognize their lack of self-efficacy and choose a more rewarding career path. Whatever the reason, simply requiring more education may have a counterproductive effect without other interventions.

Economic Stability

Determining average wages for EMS providers is confounded by a lack of distinction between the levels of certification. The average annual pay for all EMS workers is $35,670 which equates to around $17 per hour.19 This number combines Paramedics and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT) which have significantly different education, scopes of practice, and pay. Most EMTs are paid close to the federal minimum wage which would yield around $15,000 per year. With the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) for 2021 set at $12,880 per year and the practical cost of living varying from $43,000 to $60,000,20 nearly 28% of EMS providers are in the position of needing to hold multiple jobs.16

EMS providers commonly work 12- or 24-hour shifts which extend beyond traditional work hours. Many EMS agencies schedule providers for multiple shifts consecutively. When combined with commute times between jobs, the opportunity for sufficient rest is minimal. The sometimes lethal consequences of insufficient rest and subsequent cognitive decline are well documented.21 Major consequences include PAE and motor vehicle collisions both involving ambulances and personally operated vehicles.

However, without greater levels of education and clinical decisionmaking capability the market value of EMS provider work is low compared to other healthcare professionals. Reimbursement for EMS services are provided only for transportation and do not factor in medical care rendered without delivery to an emergency department. Therefore it is unlikely that simple raising wages will solve the problem of overworking without other interventions.

Built Environment

Physical activity is limited due in part to long shifts spent sitting in ambulances waiting for and responding to calls. One study revealed more half of EMS providers participating qualified as obese and did not meet minimum thresholds for physical activity.10 Many of the perceived barriers identified by the participants were consequences of other determinants such as lack of energy, lack of time, lack of resources, and social influences.

Alcohol and substance abuse used as coping mechanisms may be both related to and contributing to high rates of post-traumatic stress syndromes (PTSS)7,8 EMS providers have relatively easy access to narcotics and narcotic diversion has been an issue for some agencies in the past. However, easy access to alcohol makes it the most commonly abused substance.22 Considerable variation in reporting of PTSS symptoms may be due in part to perceptions of cultural discouragement against reporting distress.

Due to exceptionally long periods of time spent on duty, many EMS providers elect to eat from readily available sources of food such as gas stations or convenience stores. This is especially true of personnel who spend most of their shifts away from any station or base, such as during interfacility transport. The types of calorie-dense snacks and pre-packaged meals may contribute to the incidence of obesity and other metabolic disorders seen in the EMS provider population.

Social and Community Context

EMS providers have low levels of self-efficacy. The actions of the profession are guided by physician medical directors and development of the profession is under the purview of the non-medical Department of Transportation. Much of the potential clinical decisionmaking has been reduced to simplified protocolized flow charts. A culture of defensive medicine forces providers to apply inappropriate and sometimes harmful treatments to avoid punitive measures. The culture of “shame and blame”13 is pervasive, prevents the reporting of patient safety concerns, and stunts the professional development of providers.

Implications of Unhealthy Providers

As stated above, no single intervention will effectively address any single problem detailed above. While the totality of the problem must be addressed to reduce potential harm to public health, each component of the problem demands its own host of simultaneous interventions. The most likely effective strategy to “eat the elephant” of unhealthy EMS providers is to make incremental steps toward an ideal goal of provider wellness and systemic support for provider wellness. This goal will likely be achieved through a variety of policy, organizational, and individual interventions.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2018 Emergency department summary tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; May 2021.

- Boland LL, Mink PJ, Kamrud JW, Jeruzal JN, Stevens AC. Social support outside the workplace, coping styles, and burnout in a cohort of EMS providers from Minnesota. Workplace Health & Safety. 2019;67(8):414-422. doi:10.1177/2165079919829154

- Cone DC, Brice JH, Delbridge TR, et al. Patient safety culture. In: Emergency Medical Services: Clinical Practice and Systems Oversight. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2021:415-423.

- Crowe RP, Bower JK, Cash RE, Panchal AR, Rodriguez SA, Olivo-Marston SE. Association of burnout with Workforce-reducing factors among EMS Professionals. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;22(2):229-236. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1356411

- Bentley MA, Crawford JM, Wilkins JR, Fernandez AR, Studnek JR. An assessment of depression, anxiety, and stress among nationally certified ems professionals. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2013;17(3):330-338. doi:10.3109/10903127.2012.761307

- Vigil NH, Grant AR, Perez O, et al. Death by suicide—The ems profession compared to the general public. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;23(3):340-345. doi:10.1080/10903127.2018.1514090

- Donnelly E. Work-related stress and posttraumatic stress in emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(1):76-85. doi:10.3109/10903127.2011.621044

- Becker TK, Gausche-Hill M, Aswegan AL, et al. Ethical challenges in emergency medical services: Controversies and recommendations. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2013;28(5):488-497. doi:10.1017/s1049023x13008728

- Brice JH, Cyr JM, Hnat AT, et al. Assessment of key health and wellness indicators among north carolina emergency medical service providers. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2018;23(2):179-186. doi:10.1080/10903127.2018.1489017

- Supples MW, Rivard MK, Cash RE, Chrzan K, Panchal AR, McGinnis HD. Barriers to physical activity among emergency medical services professionals. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2021;18(3):304-309. doi:10.1123/jpah.2020-0305

- Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Pat Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128. doi:10.1097/pts.0b013e3182948a69

- Fairbanks RJ, Crittenden CN, O’Gara KG, et al. Emergency medical services provider perceptions of the nature of adverse events and near-misses in Out-of-hospital Care: An Ethnographic view. Acad Emer Med. 2008;15(7):633-640. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00147.x

- Crowe RP, Fernandez AR, Pepe PE, et al. The association of job demands and resources with burnout among emergency medical services professionals. Journal of the American Coll Emer Phys Open. 2020;1(1):6-16. doi:10.1002/emp2.12014

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors Among American surgeons. Annals Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi:10.1097/sla.0b013e3181bfdab3

- Rivard MK, Cash RE, Mercer CB, Chrzan K, Panchal AR. Demography of the national emergency medical services workforce: A description of those providing patient care in the Prehospital Setting. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;25(2):213-220. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1737282

- National Highway Transportation Safety Administration. National Emergency Medical Services Education Standards. Department of Transportation; 2007

- Namnabati M, Soroush F, Zargham-Boroujeni A. The relationship between nurses′ clinical competence and burnout in neonatal intensive care units. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 2016;21(4):424-429. doi:10.4103/1735-9066.185596

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook, EMTs and Paramedics. U.S. Department of Labor; 2021 https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/emts-and-paramedics.htm (Accessed: September 14, 2021)

- Glasmeier AK. Living Wage Calculator. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2021 livingwage.mit.edu (Accessed: September 14, 2021)

- Patterson PD, Weaver MD, Frank RC, Warner CW, Martin-Gill C, Guyette FX, et al. Association between poor sleep, fatigue, and safety outcomes in emergency medical services providers. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(1):86–97.

- Sterud T, Ekeberg Ø, Hem E. Health status in the ambulance services: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(1):82.